Louisiana lawmakers have overturned Gov. John Bel Edwards’ rejection of a new congressional map in the first override of a gubernatorial veto in nearly three decades, but the legislative decision won’t end the redistricting fight.

Instead, arguments over the U.S. House boundary lines that will be used in the upcoming fall elections and whether Louisiana should have a second majority-Black congressional district shift to the federal court system for judges to settle. Civil rights groups have already filed a lawsuit.

In the one-day veto session, the House voted 72-31 to override the Democratic governor’s rejection of the bill containing the congressional map, while the Senate vote was 27-11. Both chambers cleared the two-thirds vote requirement – needing support of 70 House members and 26 senators – with room to spare.

The votes largely fell along party lines, with all Republicans agreeing to overturn Edwards’ decision. In the House, three lawmakers without party affiliation and one Democrat sided with the GOP on the override effort.

The entire event, punctuated with moments of solemn debate in the Senate and a burst of applause in the House after the vote, represented a rare moment in Louisiana politics.

Lawmakers were holding only the second veto session in Louisiana’s modern history, and it was their first successful veto override ever in such a session. The House and Senate have only overruled three gubernatorial vetoes under the state’s nearly 50-year-old constitution, the prior two overrides coming in the 1990s during a regular session.

Louisiana’s redistricting battle is not unique. Courts have gotten involved in states such as Wisconsin and North Carolina amid partisan map disputes between governors and legislators. Maryland’s Republican governor vetoed a congressional district plan preferred by Democrats, only to see his bill rejection overridden by lawmakers.

In Louisiana, the Legislature temporarily adjourned its ongoing regular session to hold the veto session, prompting objections about the legality of the move from Democratic legislators who opposed the veto override.

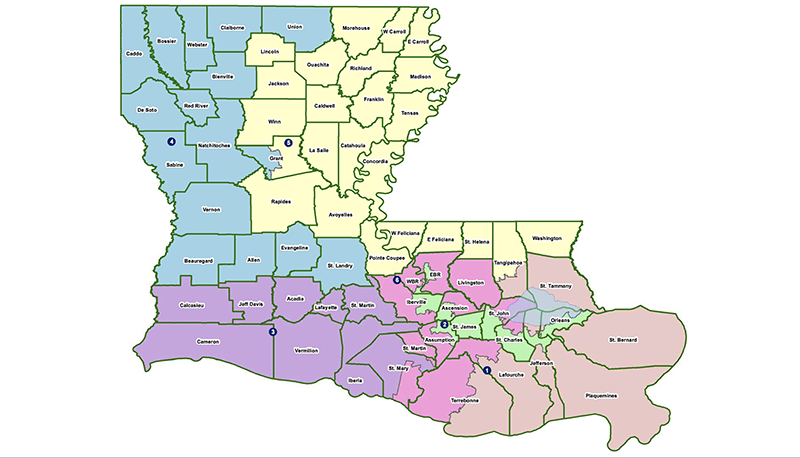

At issue in the short veto session was a congressional map passed by the majority-Republican House and Senate that largely maintains the current configuration of the six districts. The redesign expands the two northern-based seats further into southern parishes because of population shifts and maintains one majority-minority district based in New Orleans and winding up the Mississippi River into Baton Rouge.

The governor, most Democratic lawmakers and civil rights advocates opposed the map because it didn’t create a second majority-minority district. They argued such action was required under the federal Voting Rights Act because one-third of Louisiana’s residents are Black.

Republican legislative leaders countered that they believed their map followed the law. They said trying to create another majorityBlack congressional district could dilute the minority population in the other majority-Black district and make it harder to elect a person of color to the U.S. House at all. They also said such a move could break up other communities of interest.

Lawmakers passed the new U.S. House map in two identical bills in a three-week February special session. During that gathering, they also adopted redesigned district lines for the state Senate, state House, the Board of Elementary and Secondary Education and the Public Service Commission, the state’s utility regulatory body.

States must redesign their political maps every decade with the release of new U.S. Census data, to account for population changes and equally distribute their residents among elected districts as required under federal and state laws.

The boundary lines for all the districts passed by Louisiana lawmakers, which will be in place for the next decade unless a court overturns them, generally maintained the status quo. Republicans refused Democrats’ efforts to add more majority-minority districts across any map, despite the growing diversity of Louisiana’s population.

The congressional map was the only legislation Edwards vetoed from the redistricting session.

The governor allowed the new state House and Senate district lines to become law without his signature, and he signed bills containing new maps for the Public Service Commission and the Board of Elementary and Secondary Education.

Beyond the litigation over the U.S. House districts, civil rights organizations also have filed a lawsuit challenging the state House and Senate maps, ensuring that the legislative actions aren’t the end of the debate.